From Activism to Acceptance – Our Community & the Abolition Movement

The Story of A Community’s Involvement In the Abolition Movement and the Welcoming of A Slave Family

by Courtney Wilhelm

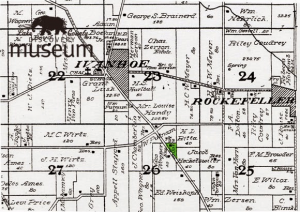

(Photos courtesy of Lake County Discovery Museum. Click on images to enlarge.)

As a fourth generation resident of Fremont Township in Northern Illinois, I grew up hearing stories about the local community. Legends, or tall tales that students in the schoolyard share with one another, stories that teachers in elementary, middle and high school tell to incorporate elements of local history. At times, even my grandparents would pass down these histories to me while pointing out houses they had lived in, schools they attended or memories from their own childhood. These stories were usually brought up in passing. No substantial recollection of specific dates, people or locations was ever provided. These stories were the product of a collective memory that was created in the community.They were a window into the past, or at the very least, a small glimpse into the version of the past the community remembered or created and passed down generation to generation.

The most notable of these tall tales was a story of a church in the community. It was rumored to be a stop in the Underground Railroad, and furthermore, a family who escaped on the hidden passage made their permanent home in Fremont Township. The family needed to live in secret until emancipation was granted with the Thirteenth Amendment. Once emancipation was achieved the family joined as equal, accepted members of this overwhelmingly white community. The curiosity that was sparked in me as a young child interested in both history and family roots, pointed me in the direction of larger historical questions as an adult. The beginnings of these questions was to explore whether this memory of a church, its participation in the Underground Railroad, and this black family was grounded in some actual historical foundations. Or, were these memories simply myth? And if by chance the truth be somewhere in the middle, what is the real story?

When exploring the collective memory of any community in the aftermath of the Civil War and claims of connections to the anti-slavery movement/abolition a historian needs to be mindful in their research. A healthy skepticism must be shown to decipher whether the memory that is being passed down is an accurate representation of the community or if it has been recreated in an attempt of the community to write itself onto the right side of history. Researching the truth that existed within the stories I was told as a child, could not stop upon discovery of the alleged family. It needs to probe deeper into the ways this story is being recreated nowadays.

The search led to a family, the Joice family. The story of this family did in many ways live up to the memory passed down to me as a child. The family did come to Illinois under auspicious terms, but not secretly as runaways on the Underground Railroad. They did make their home in Fremont Township, but they did not live in secret. In fact the life this family of four created for themselves in Fremont Township demonstrates a life of acceptance and inclusion with the white members of the community. This however points to the most significant findings of the family. Their experiences were extremely unique. Despite the collective memory that has been created, Fremont Township was not a community so progressive and accepting as to be considered an experiment in integration. The life of James, Jemima, Asa, and Sarah Joice, is a single, isolated example of acceptance. There is no doubt that the community demonstrated a willingness to undermine the institution of slavery, and furthermore, practice what they preached in terms of accepting a black family into their ranks far beyond what was common in Northern rural communities at the time. However, the collective memory that has been created fails to capture the intricacies of this family and the community at the time period. A more complete story needs to be created and passed down to represent the uniqueness of this family’s experiences in relation to the lives of other black families in the Midwest in the years following the Civil War.

From Activism

Illinois has a proud history of opposition to slavery. From its acceptance into the Union as a free state, and further connections to President Abraham Lincoln reflect a strong affinity to abolition. However, this was not always the case. Historian Merton Dillon recounts that the real push for abolition efforts in Illinois were created in the aftermath of an 1823 attempt to amendment the state Constitution of 1818 to legalize slavery. Although the attempt failed it sparked a far more widespread and organized resistance to the institution of slavery than had previously existed in the state. Much of this resistance was created within churches throughout the state.

Dillon’s findings point to an effort for recolonization of blacks from Illinois and across the country. This idea never found strong foundations in the state, although it does point to a state of mind among church circles and abolitionists in the 1820s and 1830s. Slavery was an abomination and emancipation was necessary. The quick shift from a push to legalize slavery in Illinois, to serious attempts for emancipation were precipitated by the influx of new migrants to Illinois. Dillon notes, “New settlers from both North and South who thoroughly hated slavery and wished to see the system ended… Many of these people possessed stern religious ideas which left them no easy alternative when moral decisions were involved.” Many of the new settlers Dillon points to were Methodist preachers who rode the preaching circuit in the South and were outraged at the injustices they witnessed in the slaveholding states. Seeking an alternative placement with the Methodist Church the raising population of Illinois welcomed these preachers.

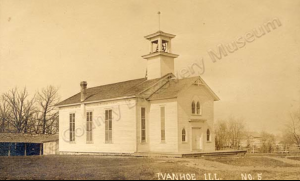

Although not a Methodist church, the Ivanhoe Congregational Church in Fremont Township, founded in 1838, reflects the findings in Dillon’s book. The church was created in a small community, with German immigrants and farmers in most northeastern county of Illinois. The opinions of the Methodist Church in regards to slavery were shared by the Congregationalist Churches of Illinois. Historian James Dorsey conducted extensive research into the Congregationalist churches in Lake County and their involvement in the anti-slavery movement. Although the degree and devotion of their efforts to undermine slavery was different from church to church they were universal in their opinion of slavery. “The first article of the by-laws of the Congregationalist churches reads, ‘No one shall be admitted to membership who does not regard the Southern slaveholding as a sin clearly condemned in the Bible’.”

Ivanhoe Congregational Church, circa 1913. During the Civil War, this congregation was outspoken in its stance against slavery. Image courtesy of private collector.

The Ivanhoe Congregational Church, where the Joice family would later become members, was one of the most active in the anti-slavery movement. In 1845 the Congregationalist churches in the Lake County area held an anti-slavery meeting in Libertyville. This meeting only the next town over reflects the strong presence of abolition feelings in the community. These feelings that would not simply be held by Church officials, but by their membership as well. In meeting with Pastor Kris Hewitt, the current pastor of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church, there is a strong feeling of pride in their beliefs and convictions of the previous membership for the position they took on slavery matters. Not only does the Church hold that they were a stop on the Underground Railroad but that their membership personally assisted in hiding and transporting runaways from one checkpoint to another on route to Canada. Additionally, the Ivanhoe Church made their position on slavery clear with a public statement reading, “we cannot but look upon slavery as a most daring sin against God, and as inflicting a perpetual torture and living death upon man.” This strong condemnation of slavery from the Church, their involvement in the Underground Railroad, activities within anti-slavery efforts makes it clear the message the Church members were exposed to, and lived their life upholding. This is crucial in understanding two aspects of the Joice family and the history in question. This strong position in opposition of slavery was passed down to a member of the Church, Lieutenant Partridge, who would later bring James Joice, the father of the family to Illinois. Eventually, this congregation would welcome the mother and two children into membership and accept them as a member of their community.

Despite the strong evidence to demonstrate the Ivanhoe Congregational Church’s involvement in the abolition movement and attempts to undermine the institution of slavery with participation in the Underground Railroad, a caution must be given. Illinois historian Larry Gara is critical of claims made by individuals and communities with respect to their involvement in the Underground Railroad. He claims that most families and communities recreated their histories in the aftermath of the Civil War to be on the “right side” of history. The credibility of these sources is threatened because the oral tradition in most of the cases he examined could not be substantiated with documentation, hard evidence, or even consistency in one oral tradition to another. Additionally, he provides examples of conflicting reports from those who claimed to be active participants in abolition efforts. He warns to be mindful and use discretion when evaluating claims of involvement because, “the inability of the abolitionists to agree… underscores the need for great caution in using such reminiscent material as a historical source.”

From what Gara has put together in his own research, it appears that published histories of the Underground Railroad in Illinois are based on oral tradition and local legend, and makes the vast system of the Underground Railroad appear far too simplistic than the reality. Furthermore he asserts, “the Underground Railroad has assumed a larger importance than it had during its period of operation, and much that was merely talk of action has been accepted as proof of activity.” David Blight further substantiates these cautions in saying that it was not just Southern histories that were recreated in the aftermath of the Civil War. It was a Northern problem as well. It seems as though the problem grew in size and scope as Northerns tried to either create or overstate their influence in the antislavery movement. “In reality, the alleged networks of ‘depots” and ‘conductors’ by which fugitives escaped to the North and in Canada had never been as elaborate as legend portrayed it.”

While skepticism may exist, embellishment of antislavery activities created, and doubts to the intensity of abolition fervor that existed in Fremont Township and within the Ivanhoe Congregational Church there is no doubt the congregation remained steadfast in their disapproval of slavery. There might be doubts to the extent of their participation as it is difficult to provide artifacts to support these claims, there remains an oral tradition that has been passed down from within the Church and the community at large. Whatever inconsistencies might exist as to the Church’s extent in the Underground Railroad there is no doubt the Church was active in resisting slavery. It is essential to keep this in mind because abolitionist feelings dating back to the Church’s founding in the 1830s help to establish a frame of mind for the congregation. The same members of the congregation that would help James Joice leave the shackles of slavery in Kentucky for a better life in Illinois. A congregation that would welcome his family into their community as equals, and later elect his son to be the first black elected official in the county. There may be doubt as to their involvement in the Underground Railroad but there is no room for doubt that a devotion to antislavery was created within the church and passed down to members of the congregation, which can clearly be seen in their assistance, reception and acceptance of the Joice family.

The Joice Family In Illinois

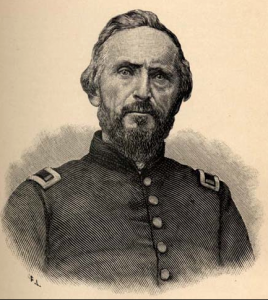

Lithograph of Addison Partridge of Ivanhoe from the “History of the Ninety-Sixth Regiment Illinois Volunteers.”

The first step in piecing together the story of the Joice family in Fremont Township, necessitates looking neither at the Joice family or in Illinois. First Lieutenant Addison Partridge of the 96th Illinois Volunteer Infantry was a member of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church. It is clear from the infantry records that the Joice family did not come to Fremont Township illegally, and secretly through the Underground Railroad. It was a chance encounter between the Lieutenant and James Joice. As a member of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church, Partridge would have been exposed to the antislavery rhetoric and moral compass that existed from the Church’s founding and within the Congregationalist denomination’s values.

The historical records for the Joice family begins in October 1862, in Scott County, Kentucky. James Joice crossed Confederate lines and made his way to the Union camp. Within the camp, members of the 96th Illinois Volunteer Infantry were positioned. The regiment’s records indicate that these men were open in their hatred and disgust of slavery. However, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 made accepting slaves as workers within a Union camp highly illegal. Despite their stance on slavery and wanting to assist slaves, the fall of 1862 was not the appropriate time. Furthermore, a border state like Kentucky, Lincoln was hoping to keep within the Union fold, was not the appropriate place. Leslie Schwalm in Emancipation’s Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest outlines that border states presented a unique challenge for the President Lincoln at the start of the war. He hoped that a position of neutrality by the federal government on the issue of slavery in border states would encourage those states to stay loyal to the Union and hopefully persuade Southern Unionists to help defeat the Confederacy.

At the start of the war slavery was shaped by politics just as much by military campaign or conquest. The Emancipation Proclamation would change the course of the issue, but at the time of James and Lieutenant Partridge’s encounter in 1862, the relationship that was created was both illegal according to the Fugitive Slave Act and in defiance of Union policy as outlined by President Lincoln. When Partridge succomed to a camp fever that he was not able to fully recover from. When he returned Fremont Township due to his illness, James Joice went with him. James lived for the remainder of the Civil War in Fremont Township. When the war was over he returned to Scott County to bring the remainder of his family to Illinois.

When James Joice returned to Illinois he brought with him his wife Jemima, his son Asa and his daughter Sarah. James was twenty years Jemima’s senior. Based on research conducted by the Ivanhoe Congregational Church it appears that Jemima was James’ second wife. Additionally, Sarah might not have been related to the other three family members. In keeping with what would have been common for slaves at the time, when Sarah’s mother died during childbirth she was taken in as their own by James and Jemima. Sadly, much of the historical record about the family’s experience in Kentucky is lost. What is known about the family’s life in Kentucky has been passed down through generations as an oral tradition when Jemima, Asa and Sarah became integrated members of the church. Their story survives in such a robust way because of the information collected by the Church and local historical agencies.

The 1870 Federal Census is the first time the family appears within a Census record. They are shown as living in Fremont Township and the family’s occupation was listed as farmer. While the Census record only provides a small glimpse into the family’s life, the Census records do serve as a checkpoint of sorts to show the family’s progress overtime. The last piece of important information from this record showed that the family lived in a home they rented. Creating a life for your family in a new community only a few years after freedom was achieved is certainly a daunting task. A task that millions of Americans made in the years after the the Civil War. The Joice family was not alone in their migration North, nor were they alone in the struggles they faced trying to build a prosperous life.

The migration of blacks to Illinois after the Civil War makes it clear that the Joice family might have been unique in their journey or circumstances that brought them to Illinois, but they were not unique in seeking it as a final destination for their family. In 1860, Illinois has a population of just over 1.7 million people, of that, only 7,628 were black. In 1870, it increased to 2.5 million people and 28,762 blacks. At the beginning of the twentieth century, in 1900 the state population was nearly 4.7 million people and of that 85,078 were black. There is clearly a trend present, and Illinois became one of many states newly freed African Americans sought to make their new life in the decades after the Civil War, long before the Great Migration of the twentieth century associated with booming wartime industries that drew many African Americans from the South to northern industrial centers.

While the Joice family was not unique in moving to Illinois, they were unique in living in Fremont Township and the surrounding area. The surrounding townships show little to no black population as of 1870. Libertyville; 2, Vernon; 1, Wauconda; 0, Warren; 8, Ela; 0, Cuba; 0, and Grant; 0. In the entire county in 1870 there were only 75 blacks, of which 4 were actually Native American, but were classified as black by the Census recorder. It is essential to keep in mind while examining the experiences of the Joice family, their experiences in many ways fit into a larger narrative of African Americans, their opportunities and experiences like other African Americans in rural Illinois, or the Midwest cannot be simplified to generalizations.

In 1872 James Joice died. The Waukegan Gazette ran a statement in the “Obituaries” about the passing of James, “He leaves a wife in destitute conditions.” This points to a very rough transition for the family in their first few years in Illinois. Knowing that the family was left in destitute conditions along with the information in the 1870 Census that the family was renting their home points to a very bleak start to their new life in freedom. Keeping these facts in mind, it will make it all the more impressive what the family is able to accomplish in a few decades of making their home in Illinois.

To Acceptance

Later Census records show improved opportunities for the family in the years since James’ passing. This was aided by the fact that the family was welcomed by both the Ivanhoe Congregational Church, but also into the community. The 1880 Census marks some unique developments for the family. The Joice family does not show up in the record in Fremont Township. Asa Joice is listed individually as living in Libertyville Township. It shows that his relationship to the head of the household was “servant” and he listed his occupation as farm laborer. This presumably demonstrates an economically advantageous situation for Asa to leave his sister and mother. It is unclear why Jemima and Sarah did not appear in this census, but without a male in the household they might have been reluctant to participate.

Unfortunately the 1890 Census was burned in Washington D.C. and left researchers, historians and genealogists with a hole in the historical record. While the absence of this document presents some challenges in piecing together the life of the Joice family, this time period is not without resources. For a couple of reasons the Joice family can be placed in Fremont Township throughout the 1890s. Jemima was accepted into membership of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church on March 5, 1876, followed by Asa and Sarah on May 6, 1877. This establishes a strong connection between the family, the Church and the local community. Additionally, all of the family members were active in the church and its activities, attending services and prayer groups weekly. Church documents citing that they family was so frequently in attendance, that when they were unable to attend, the services didn’t feel the same in their absence.

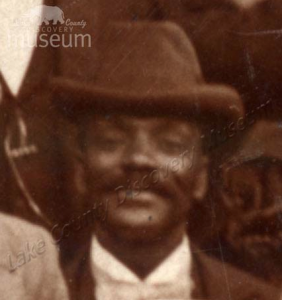

Christian Endeavor Society picnic on the grounds of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church, 1897. Asa Joice is seated in the middle to the right of center, and his mother and sister are standing to the far right.

The Church created a sense of acceptance for the Joice family that makes their inclusion into the community a special story. A newspaper article that ran in the Daily Herald in 2001 provides a fascinating picture of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church and its members at a picnic in 1897 for the Christian Endeavor Society. Fifty or so members wearing their finest Victorian style clothing representing a level of wealth and class that was unattainable for most in the country at the time. Also in the picture are the three members of the Joice family. They are not segregated and off to the side as if given token credit for their membership to the church. They stand within the ranks of the other members of the Church. They too are dress in Victorian style clothing. Although the picture makes it clear that their suit and dresses are not the same quality as the other white members of the Church, that detail is not as important as the larger message of the picture. The Joice family was free to associate and socialize with members of white society, at a gathering as personal as a religious function.

The absence of the 1890s Census makes it difficult to place the entire family in Fremont Township or even under the same roof. In 1880, Asa was listed as living in Libertyville, away from his mother and sister. However, Asa would raise to a level or prominence and acceptance that puts him in selective group of African Americans in the last half of the nineteenth century. Asa held a variety of public offices for Fremont Township beginning in the late 1890s through the first decade of the 1900s. The positions varied in significance, time commitment and compensation. Holding these positions would have required that Asa live in Fremont Township, so despite the absence of the 1890 Census, it is evident by the later half of the 1890s, he had moved back.

On April 2, 1889, Asa Joice was elected Town Constable. Essentially, Asa served as a law enforcement officer. The community was not large enough to need any sort full-time police force. In this role he would have arrested those with a warrant to their name, and organized their transport to and from the county seat in Waukegan. On one occasion Asa arrested a local resident of Fremont Township who lived off of Gilmer Road. The man was accused of stealing a horse. Asa was responsible for taking the man into Rockefeller (now known as Mundelein) to enter his plea. Upon his guilty plea, Asa took him to Waukegan to admit him to jail. Serving as Constable, Asa proves that he had been accepted by his community, and not for a minor job, but one as a deputy of the law and therefore an extension of the government.

Asa would later serve in many other government positions throughout the late 1890s and into the 1900s, the longest serving position as a member of the Highway Commission. From 1909 to 1914 he served as the Highway Commission President. His responsibilities included overseeing the development of new roads. This could be clearing way of wildlife for the eventual construction of new roads in the township at a time when the township’s population was growing steadily. Additionally, Asa served as the Thistle Commissioner. In a community based on farming, thistle was a nasty weed not indigenous to the area that would suffocate local vegetation. The Thistler Commissioner was responsible for clearing away thistle if property owners did not take care of this on their own time. The Commissioner would be sent to take care of the issue, and be compensated for their work and time. Later, the property owner would be billed by the township for not taking care of the problem, because if left untreated it could threaten the livelihood of other farmers in the community.

Examining the “Auditor’s Record” in the Fremont Township offices also point to Asa serving in election related roles, and satisfying other odd jobs for the Township. Asa served as an election judge a variety of times. He was also compensated for “caring for election booths.” I would presume that this meant building new election booths or maintaining ones already constructed, however the ambiguity of the title makes it hard to know for certain. Knowing Asa’s background in farming and serving as a farm laborer, as a slave of course, but additionally as a hired hand to people in Libertyville and throughout Fremont Township, this is a job he would have been able to complete rather easily and well given his extensive skill set.

The most fascinating thing about the transformation of the Joice family from slaves to accepted members of the community comes not only in Asa’s election to various township offices. The political success of Asa is matched in the economic progress of the family throughout the same time period. The absence of the 1890 Census is a great void in the family’s story. But, despite its loss, it is clear that the family’s life was improving greatly from “destitute condition” they were left in when James died. The 1900 Census shows Asa as the head of the household. Sarah and Jemima are sublisted under Asa. While it shows that Jemima was having difficulty finding steady work, she listed that she was unemployed twelve months in the previous year, Sarah was never unemployed in the previous year. Sarah was working as a “housekeep.” The most significant finding in the Census shows that family had a mortgage in their name. It was listed as a farmhouse, farm schedule #166. (Unfortunately, Farm Schedules were housed in the same building in Washington D.C. with the 1890 Census and these records have also been lost.) Even though it is difficult to know the size of the land, the quality of the land, and what the family was using it for, this discovery is still very significant. The family was able to achieve a level of success that afforded them the opportunity to buy their own farm and operate it independently.

By the 1910 Census the family appears to be experiencing even more economic success. The family was listed as having a new property, identified as Farm Schedule lot #92. This property was also listed as a farmhouse and with Asa listed as the head of the household he identified his occupation as general farming. This last property was about ten acres in size and not more than two miles away from the Ivanhoe Congregational Church, where the family remained active members of the Church. The opportunities for the family extended beyond economic advancements. In previous Census records Jemima listed that she could not read or write. For the first time in the 1910 record Jemima lists that she is literate. This is the first time all members of the family demonstrate that they can read and write. While this might not seem like a huge advancement it does signify a sense of freedom that Jemima would previously have been denied. No longer would she have to rely on others to help complete tasks, the ability to read and write would afford her a sense of independence and accomplishment.

The Church was the one place despite the moving between neighboring towns and properties that remained constant for the family. After being accepted into membership in the 1870s the family members each took active roles in church activities. Sarah and Jemima remained active not just in weekly services but also on Wednesday night prayer groups. Likewise, Asa took an active role. He was elected Church Secretary in 1890 and 1891, and Sunday School Treasurer. When the mission Sunday School was reopened, Asa was elected superintendent. Asa’s call to leadership is evident time and time again. Not only in political realms but within a religious calling too. The Christian Endeavor Society was a group founded in 1881, that took up a variety of causes, among them the temperance movement. Asa was elected as the president of the local Christian Endeavor Society. Although Sarah did not have a position within the organization, when Asa and other members of the Christian Endeavor Society would travel to other local churches and educational groups, Sarah was always in attendance. These details about the family’s involvement in local church activities are important in understanding the Joice family because it demonstrates that they were not just members of the church. There names on the Church ledger extended beyond words on a page. Their membership was felt both in the pews on Sunday mornings, weekly prayer groups on Wednesdays, building stronger church networks in neighboring communities and participating in Church gatherings.

James, Jemima, Asa and Sarah are buried in the Ivanhoe Church Cemetery on Route 176. Ivanhoe Cemetery, circa 1918, (LCDM 2003.0.26)

Sadly, the historical record for the family begins to fall apart after the 1910 Census. With the outbreak of World War I and the impending flu epidemic, Jemima was active in taking care of people and children in the community. Serving as a housekeeper and nurse to people in need, Jemima ultimately contracted the illness herself. She died in 1920 while trying to assist others back to good health at the age of 86. Asa is not listed in the 1920 Census for unknown reasons. Asa would die in 1924 at the age of 64. Sarah would live for many more years alone. In the 1930 Census she was listed as renting a home, and she is the only name listed in the household. In examining the address she provided to the census Recorder it is evident that the home she resided in was about half a mile to the Church. In the passing of her own family, the Church family remained an important connection for her to maintain. She died in 1941 after suffering from a stroke and living in poor health for a number of years. The Joice family members are buried together in the cemetery of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church, integrated even in death, with other members of the congregation and community of Fremont Township.

Revising and Correcting the Historical Narrative

It is evident the story passed down to me as a child had several inaccuracies. But, the real story of the Joice family proved to be just as exciting as the stories I was told. From a historian’s perspective uncovering the real story of the Joice family is only the beginning. The next step is to explore what attempts are being made to correct the collective memory of this community to represent what really happened to this slave family when they moved to Illinois. Fortunately, within the last decade huge improvements have been made in restoring the collective memory of this family to a more accurate and truthful position.

The 1970s are the first time significant contributions to the historical record about this family are evident. Pastor Delbert Shrag conducted his own research of the Joice family after talking with members of the congregation about the Church’s history. The research was extensive in looking at both Church documents and secondary sources within the community. Additionally, in 1976 the Independent Register, an newspaper that has since gone out of business ran a series, “Profiles of the Bicentennial.” The purpose of the series was to profile people from the community of the readership, which consisted mostly of Fremont and Libertyville Township. In both instances, errors in the story passed down to me were corrected.

The late 1980s and 1990s saw further publication about the Joice family and corrections to the collective memory. Local community college professor published the book Up South, which examined the involvement of antislavery efforts throughout the suburbs of Chicago, including the activities of the Ivanhoe Congregational Church. Also, he profiled significant blacks from the same area, and Asa Joice was included. The work of Professor Dorsey along with the work of local historians like Diana Dretzke whose work is evident in the resources available at the Lake County Discovery Museum and in the online archives of Lake County have helped in shifting the focus of this family’s story away from the misconceptions and myths and centering their story around their real experiences. Dretzke’s work is perhaps the most extensive as she has created a online blog postings about Lake County history, including the story of the Joice family. Additionally, she writes for the Daily Herald on local interest pieces and whenever possible the includes the Joice family and their presence in the community.

A perplexing problem still remains. The work of many different newspapers, authors, Church members and local historians predates the time frame I was told these stories. I heard the inaccurate stories of the Joice family in the late 1990s and early 2000s when I was still in grade school. Much of the secondary research I collected was published before that time frame. The new obstacle that needs to be tackled is not understanding the Joice family’s real story. That story has been researched and collected from many different people and perspectives. Now the issue is passing this story down to alter the collective memory of the community and to reflect the real experiences of this family. Piecing together the story of this family 150 years removed from their migration to Illinois is a difficult task, but it appears the most difficult task will be changing the way the community remembers this family. There is hope if younger generations can accept the real story of the Joice family and allow the misconceptions to fade away, and give way to the truth.

Conclusions

Walking through the Ivanhoe Congregational Church cemetery on a chilled spring day, I examined the names on the gravestones. I see the names Brown and Wilhelm, marking the final resting place for grandparents and great-grandparents who told me stories about their life in this community. Not far away Partridge, who helped bring the Joice family to Fremont Township. Farther down the path, the family burial plot for the Wirtz family, and many other families whose names appeared as elected officials in the “Fremont Township Auditor’s Record” and “Highway Commissioner Record.” The same families who sat beside James, Jemima, Asa and Sarah at church. If you’re not careful, you might overlook the gravestone marking for the Joice family. The final resting place for a family who had lived through unspeakable horrors and hardships, only to create for themselves a new life. The Joice family might not have been equal to others when they took their first breath, or in the first few years of their life. But this community accepted them as equals and that is symbolized forever in the final resting place for the family and their congregation.

A new life that enabled the family to read and write, and the freedom to express themselves in a way previously denied them. New opportunities to become landowners and commanders of their own fortune, instead of slaves to another man’s greed. The recognition and respect of a community to not only be welcomed as a man worthy of casting a ballot like any other, but a man whose character and worth made him stand out among those peers as possessing the qualities of a distinguished elected official. The same man who decades earlier was bound in the shackles of slavery, only to achieve emancipation and hold public office in la nearly thirty year time span. The stories that I was passed down as a child might be incomplete, and in many cases wrong. The family did not escape on the Underground Railroad, but they were admitted to a church of strong moral character and activism as equals. The tall tales I was passed down as a child certainly sparked by interest and curiosity. But the real story is much better.

To say Fremont Township was an open experiment in integration is wrong. There is not enough evidence to support that, and frankly it would need to be substantiated with a larger presence of black families, not simply the Joice family. However, there is enough to say that the Joice family was accepted economically, socially and politically by their church and surrounding community. And despite whatever doubts historians may have about community involvement in the Underground Railroad and the caution that needs to be used when examining these claims, there is no doubt that the Ivanhoe Congregational Church was active in resisting slavery, and when the opportunity came to practice what they had been preaching, and to welcome a black family as they would a white family, they did so willingly. It will take time for the collective memory to reflect the real story of the Joice family, but the work of Church members and local historians gives hope that the real story has been collected and substantiated and now needs to be accepted and retold to right the wrongs in the community’s memory.

NOTE: Fremont Township’s Asa Joice was the first elected African American in Lake County.